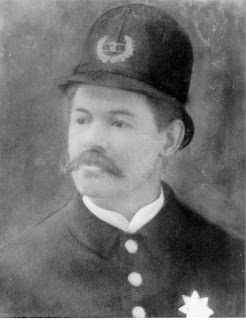

The Death of Police Officer Charles S. Ford 1907

Preface

The decision of the heirs of James Hegney’s estate to transfer management of the Albany Hotel to others may have been prompted by the publicity surrounding the shooting of a police officer by bandits who held up the Albany Saloon in December 1907. The death of Police Officer Charles S. Ford shocked Salt Lake City and reinforced the belief that West Second South had become a dangerous section of the city.

Sensational

newspaper accounts detailed that three men named Joe Garcia, John Owen, and

Joseph Sullivan were involved in the robbery and shooting of Policeman Ford. However,

only two of these men were actually in the Albany saloon and associated with

the killing of the officer. The official version nonetheless was that the two

“hardened criminals” Garcia and Sullivan, known to the police, were responsible

for the robbery and shooting while Owen was merely a lookout. That was John

Owen stated version that he told to the police shortly after he was captured

yet circumstantial evidence placed Owen within the Saloon.

Eyewitnesses, who

were within, the saloon during the “hold-up” also gave conflicting statements

on the physical characteristic of the robbers and ethnic prejudice may have

been a part of the confusion to who really was the actual shooter of Officer

Ford.

Additionally the police were under immense pressure to solve the crime involving the death of a fellow officer and in their haste may have pinned the murder on the wrong suspect. Once the “official” version was decided on all evidence was made to conform to the official version. The public demanded an accountability for the killing of a police officer no matter who. Whatever may be the true story of who actually participated in the Albany Saloon hold-up and was involved in the shooting of Policeman Ford may never be known.

PART ONE

Chapter One

Charles S Ford was a native of Vermont, married in New York State, and moved from Kansas to Salt Lake City in 1889. The first mention of him in Salt Lake City newspaper accounts was in 1890. He was mentioned as a drummer in the Liberal Military Band and Orchestra as part of the Drum Corps. The Liberal Band was formed in 1889 to support candidates and positions of the Liberal Party which was formed to oppose Mormon domination of Utah politics.

In 1890 Ford also became a partner

with C.L Crane and Charles F Reynolds in a “variety theater” enterprise called

C F Reynolds and Company. The variety theater was located on Franklin Avenue,

today’s’ Edison Street; a narrow street cutting north-south through City Block

56.

A variety theater in Nineteenth

Century’s jargon was a type of venue where various performances and events

occurred ranging from theatrical plays to boxing events. The theater was

constructed just north of Hattie Wilson's brothel at 53 Franklin Avenue, at the

cost of $20,000. The building still stands today after servings stints as the

“Salvation Army's Workingman's Hotel, a brothel, and a print shop, among other

uses.” It is now numbered 231 South Edison Street.

Franklin Avenue in 1890 had not yet

become the location of many of the city’s brothels and the home to the African

American population. It was a narrow street occupied almost exclusively by

residences. However in 1890 Franklin Avenue was “notorious” for having a

"variety theater" just a few

feet north of Hattie Wilson's Brothel at 53 Franklin. The theater, besides

vaudeville shows, was rumored to hold illegal prize fights, and there were

claims that prostitutes solicited men there and even performed sex acts in the

booths. .

Charles Ford’s business partner,

Charles F Reynolds was issued a theater license in 1890 with the express

understanding that “no intoxicating liquor should be retailed in the building”.

Objection to granting a liquor license was that the theater was within 330 feet

of a public school and two churches. Additionally there was a saloon opposite

to the theater already which was deemed “to be sufficient to supplies all

reason demands.”

However, almost immediately

Reynolds applied for a liquor license to sell beer in a saloon in the basement

at performances “attended almost exclusively by males.” Thus the businessmen

wanted to serve beer especially when boxing ring fights in the theater

occurred. Several well promoted major boxing matches were held at the Franklin

Avenue Theater during 1891.

Newspapers reported several plays

and other vaudeville acts being performed at the Franklin Avenue Theatre as

that the company had a stage manager and an orchestra leader. It advertised

itself as “Open every night with a strictly First Class Entertainment- The

place to spend a Pleasant Evening- Admission 25 and 50 cent.”

The business partners of the

theater fought and lost a long battle for a saloon license. Those opposed to

granting the theater said their intentions were “to preserve the morals and

happiness of the people of the neighborhood.” After the city council denied the

owners a license several times they appealed to the Utah Supreme Court which

ordered the council to grant them one.

The Franklin Avenue Theater’s legal

issues acquiring a liquor license eventually caused the enterprise to fail in

late 1891. The business owed outstanding debts to gas and electric utilities as

well as to local businesses. In August 1891, the building was even padlocked

for a month after being sued by the gas and light companies. The theater

reopened but by 1892 Charles Ford had left being the proprietor.

The 1892 Polk Directory for Salt

Lake City listed Ford as a policeman residing at 139 Second East when he was 36

years old. His daughter later recalled that he served a year without

experiencing any trouble. Angry over the death of her father, a daughter said,

“He was a policeman fourteen years ago [1894] and was on the force for more

than a year without having any sort of trouble. And now only a few days after

his return to the police force he is shot down. It was wrong to place him in

such a dangerous neighborhood just as soon as he returned to the police force.”

Ford only remained on the police

force a year and in order to support his family he changed careers and became a

builder and contractor by 1893. He also moved into a home at 531 South Second

East which was his residence for the remainder of his life. While his

occupation, in the Polk Directory, was listed as a carpenter and a contractor

from 1893 until 1907, newspaper accounts referred to Ford as a “well known

millwright and builder” and a “successful and veteran mill builder” for various

mining operations.

During the time Ford worked as a

contractor he became a member of the Fraternal Orders of Benevolent and

Protective Order of Elks, the Knights of Pythias, and the Woodsmen of the

World, a large privately held insurance company.

Ford was also extremely interested

in music and for years had been a member of the Liberal Party Band and the Held

Military Band, as a “snare and trap drummer.” He was a drum major for these

bands and “was a familiar figure as he led in marches in the streets.”

Ford must never have given up his

thoughts of being a law officer as that in 1905 at the age of 49 he became a

“special United States deputy” working on the Native American Reservation near

Vernal, Utah for a month. Again in 1906 he was a deputy United States Marshal

given the task of trying to locate a wanted polygamist named Thomas

Chamberlain. He tried but failed to serve Chamberlain with a subpoena as that the

polygamist had been ordered to appear before the United States Senate Committee

on Privileges and Elections in relation to the Reed Smoot hearings to determine

whether polygamy was still being practice in Utah after the Mormon 1890

Manifesto.

Charles Ford only appeared twice to

have his own run in with the law; both times in 1891 and 1898 and both times

having to do with assault. In 1898 a brief mention in the newspapers reported

that he paid a fine of $15 for assaulting Peter A Bergquist. The 60 year old

Swede stonecutter was a neighbor of Ford but what lead up to the altercation

was not reported.

A more serious assault occurred

seven years earlier in August 1891; which made newspapers detailing the event

that occurred during a political rally and parade. Ford assaulted an electric

car motorman for failing to stop his trolley while a procession of the Liberal

Band crossed the railroad tracks on Main Street and Second South.

A motorman named George R. Crow was

operating car No. 34 on the Twenty-First Ward line in the evening of

altercation. Charles Ford was in charge of the Liberal band that night and was

at the head of the procession “about five feet ahead of the fifers.”

As the marching band was crossing

the street he saw the electric trolley coming towards the intersection where

the band members were crossing. He said later that he “would have halted the

procession if he had observed the danger sooner.”

He said he called out to the

motorman to stop the car and when the trolley kept approaching Ford jumped on

the car twice saying he “would have averted the danger if he had not been

pushed off” so he “had to use force with his baton.”

Crow stated he was coming down Main

Street on 9:30 that night at a “very slow rate” at a speed of 5 miles an hour

when he noticed eight members of the drum corps in front of the car and

dangerously close to it when the car broke through the line as the Liberal drum

corps crossed the tracks. He rang his bell and slowed up as much as possible

but came so close to one that a “drum was twisted from the drummer.”

A man named Clark Lowry who was on the trolley car with Crow, said

they were moving slowly up Main Street when Ford jumped on to the car and said,

“you son of a bitch stop this car.” Ford insisted that he never used such language.

Ford twisting the trolley brake was then pushed off the car by Lowry to prevent

Ford from shutting off the electric power. However Ford jumped back on to the

platform and struck Crow a “terrible blow” on the left temple with the heavy

end of the drum major staff. It left Crow a “lump as big as a hen’s egg.

Crow recovering from the blow

stopped his Trolley car and left it to

find the identity of the man who struck him. He followed the “drum beaters”

down Second South and around the Union National Bank Corner. Here the corps

broke ranks.

Ford was walking along “with the

boys, his coat on his arm and his baton in hand when a friend said, be on your

guard there’s a fellow following you.” Ford turned around and stood face to

face with the motorman. He asked, “ Are you looking for me and Crow replied, “Yes I want to know the son of a

bitch who struck me.” Crow denied using

those words. When Ford heard Crow confront him, he “landed a blow on his face”

followed by a “succession of right hands which knock Crow over a bicycle into

the gutter.”

Crow seeing he had no friends in

the crowd retreated up town followed by a howling mob yelling “jump him” and

“kill him.” The motorman hurried away, with the crowd hurling at him anything

they could lay their hands on.

Eventually someone assisted Crow

and helped him reach the Deseret Bank corner where the Salt Lake City Rail Road

street car company Superintendent Walter P. Read ”took a hold of the motorman

and hurried him into the company’s office in the Hooper Building .” The angry

mob now increase to about fifty and threatened to take Crow away from Read who

summoned three other company personnel to help keep the crowd back.

Superintendent Read ordered the doors to the company closed and told the crowd

they could not enter.

A moment later a police officer

appeared with Ford, who was under arrest, taking him to the sheriff office in

the same building. Superintendent Read asked the police officer to assist him

and his men at keeping the crowd out of the building. The mob pushed,

threatened, and swore to be let in until the police office drew his pistol and

commanded them to fall back.

Ford was charged with assault and

immediately bailed out. Upon his reappearance The “sentiment of the mob changed

with his release.”

At Ford’s police court

hearing, there was “standing room only”

by his supporters. George Crow testified that he stopped the electric current

to the trolley “as soon as he could.” The judge then ruled that Ford had “no

right, no matter the provocation, to

strike a man with such a weapon as the baton he held in his hand.” The court

fined him $50 which Ford appealed. In March 1892, he went before the Third District Court which

found Ford guilty of assault also and he was fined $50 plus court costs.

Charles S. Ford pursued his

ambition to become a city police officer again and in November, 1907, Salt Lake

City Chief of Police Thomas Pitt announced his appointment to the police force

along with others. It was noted that none of the new hires were known to be

affiliated with the Mormon Church, including Ford who was hired to fill the

vacancy caused by the resignation of Officer C.M. Evans.

However Ford’s confirmation was

held up by the head of the Police and Prison Committee for political reasons

because the head of the committee had not been consulted. As that the city was

dominated by the progressive American Party the chairs of the districts to

which the officers were to be assigned needed their approval.

The Police and Prison committee

finally approved of Police Chief Pitt’s hires ,and the Salt Lake City Council

confirmed the hires on Monday December 9, 1907. Policeman Ford’s first day on

the job was early Tuesday Morning after midnight having been assigned as a

night watchman for a beat in Greek Town.

Chapter Two

The Fencers; Tip and Sadie Belchers and Sneak Thief Joe Garcia

George “Tip” Belcher [1882-1940]

was born in Jefferson County Colorado. His father had been the Sheriff of

Golden, Colorado and in 1882 when “Tip” Belcher was born his father was

employed as the United States Marshal for Denver. When his father left being a

law officer, he became a detective for the Rocky Mountain Detective Agency.

However “Tip” did not follow in his father’s peace officer footsteps but rather

became a career criminal.

Tip Belcher stated he had been a

bartender since he was 18 years old beginning in Denver, Colorado. In 1902 George Belcher, and

22 years old Eddie Condon, were wanted in Denver on a charge of burglarizing a

drug store. They had escaped from the city jail by crawling up some steam pipes

and cutting their way out through the ceiling. “They were assisted in this by

the fact plumbers at work in the jail had left some loose boards in the

ceilings.”

After three days on the run the

young men were captured in Colorado Springs when they were seen leaving the

Produce lodging house on Huerfano Street. Belcher was sentenced to five years

in the Colorado State Reformatory at Buena Vista. If he served his entire

sentence Belcher would have been in prison until 1907. However Belcher stated

he had “been in prison many times.”

Sometime by 1907 “Tip” Belcher was

living with a woman identified only as “Mrs. Sadie Belcher”. Whether they were

actually married or not is not clear, as that prostitutes often used the

respectable title of “Mrs.” While there’s no evidence to suggest Sadie Belcher was

a “demi-mode” she certainly would have been known as a “loose” or “lewd” woman.

Sadie Belcher was described by

reporters as “pretty” and as a “trim

little woman with a mass of blond hair” but not much else is known about her.

She was most likely in her early twenties. Sadie may have been a pseudonym as

no information has been located to indicate when or where she was born.

After “Tip” and Sadie Belcher relocated to Salt Lake City from Denver, Colorado in 1907, he was employed as a night bartender at the Jubilee Saloon at 28 Commercial Street. He and Sadie rented quarters at 150 North Main Street in a portion of the old Heber C Kimball house. Kimball had been a counselor to Brigham Young in the Nineteenth Century and a Mormon Apostle.

|

| Kimball Lodgings |

Tip Belcher stated that he came to

Utah in October 1907 from Denver but perhaps earlier as that a longtime friend

and ex-convict named Joe Garcia had been rooming at his place before the

December 14 robbery and shooting. The police believed that Garcia had been

operating in Salt Lake City since August.

“Tip” Belcher was known as Joe Garcia’s

“fence” or receiver of stolen items. He also acted as a middleman between a

series of thieves in Denver to whom he sold jewelry stolen in Salt Lake City.

Items stolen in Denver were sent to Utah to be pawned in the many unlicensed

pawn shops in Salt Lake City. Belcher admitted to having received watches that

had been stolen in Denver and sent to Salt Lake City to be sold.

|

| Joe Garcia |

Garcia’s physical appearance may

have been why Garcia was described as “swarthy” and his “complexion so dark

that he was thought to be an African America.” However, the newspapers of the

period consistently referred to him as a “half breed” Chinese-Mexican.

Garcia was tall, for men of the

times, about five feet and nine inches in height and he was called clever and

intelligent by those acquainted with him. Joe Garcia was also rumored to have

been Sadie Belcher’s lover and she his mistress.

In court testimony given in 1908,

Tip Belcher said he became acquainted with Garcia when they both in jail in

Denver. Belcher testified that he had known Garcia for about 8 years which

would have been in 1900 when Belcher was 18 and Garcia 20 years old. probably

that was not accurate.

In the first few years of the

Twentieth Century, Joe Garcia, known then as “Cuaz Cordova” was arrested and

sentenced to a term of two to four years in the Colorado state prison at Canyon

City. He had been convicted of a “felonious assault with the intent to commit

murder.”

In June, 1903, Garcia “made a

sensational break for liberty” at Canyon City along with five other convicts.

The six convicts made their daring escape by taking two prison workers and the

warden’s wife as hostages, “holding the woman as a shield.” The convicts blew

up the prison gate with dynamite to make their getaway but when guards fired

upon them from the prison walls one of the inmate who was the ring leader was

killed and another was seriously wounded.

Garcia along with another convict

managed to make it into town and stole some horses. The pair made it a

“distance of three miles from the prison before he was shot in the foot,

captured and brought back to the prison.”

Garcia was whipped as a punishment for trying to escape and then

confined to the prison dungeon for sixty days consisting only on bread and

water.

When Garcia actually came to Salt

Lake City is not clear. Some accounts stated he was in the city as early as

August 1907 while Tip Belcher said Garcia

only stayed with him since November. The Belchers nevertheless

“sheltered him” at their Kimball residence allowing him to sleep on the floor

during the day. He “would lurk there in the day and prowl at night.” Garcia

slept fully dressed with a gun at his side while residing at the old Kimball

place.

During Garcia’s stay in Salt Lake

City, he was burglarizing homes of wealthy residents of the Capital Hill area

and in the nearby “Avenues” section of northeast Salt Lake. He would climbing

onto porches and enter residences through unlocked widows. As that this was his

main “modus operandi” Garcia was referred over and over again as “the Porch

Climber.”

In the months that Garcia was in

Salt Lake City, he was “making a success of carrying off thousands of dollars’

worth of jewels from Salt Lake Residences. Garcia operated extensively robbing

the homes of wealthy Salt Lakers at night while hiding out at the Belcher’s

residence during the day. He “looted the residence of Richard H. Millett, the

mining man, of 559 Brigham Street [ now South Temple],” J.J. Daley, of the

Daly-Judge mining company, at 319 Brigham Street and many other well know men.

He had even taken a watch from the home of Mrs. L.A. Evans of 139 A Street, who

was the daughter of Salt Lake City Mayor John S. Bransford. Garcia gave the

stolen loot, mainly watches and jewelry,

to Tip Belcher who would send the items

off to Denver to be sold by his underworld associates there.

Chapter Three

Joseph Sullivan [1879-1918]

Joseph Sullivan was a

native of Washington State probably of Irish parentage. He was described as

having an “athletic build; full of strength and vitality” and his inmate photograph taken in 1903 at the

age of 24 showed the likeness of a handsome young man.

Sullivan’s prison booking description

from 1903 stated was that he was five feet and 9 ½ inches tall, weighted 147

pounds, his shoe size was 7 ½, and hat size was 7 ¼. His eyes were listed as

“blue gray” and he had brown hair. Identification marks were that he had a

large vaccination mark and a wart upon his upper right arm. There was also a

scar on his left eyebrow and his teeth were described as bad.

After he had been in the Utah state

prison between 1903 and 1907 he had a snake tattoo inked on the underside of

his right wrist. This tattoo mark would puzzle the Portland Police when

Sullivan was arrested there in 1908 as it had not been included in the

description of the man when incarcerated in 1903.

Sullivan said that as a young man,

around 1898 when he was about 18 years old, he traveled to Panama where he

worked on the construction of some inland bridges. From there he went to the

city of Manzanillo on the Pacific coast of Mexico from where he went to

California.

In San Francisco Sullivan worked on

the vessels plying the coast trade for a couple of years. Sullivan testified “I am a sailor but have never been

in the navy. All my voyages have been aboard ships of the merchant marines.”

Sullivan having been a seaman was said that he could “easily be recognized by

his walk.” He was still known as a “sailor” by Utah penitentiary guards who

knew him well long after he left the sea.

After leaving working on merchant

ships, Joseph Sullivan, like thousands of other unemployed men, ended up in

gangs of “hoboes” stealing rides on freight trains crisscrossing the west,

looking for work or simply begging for handouts. Sullivan was identified as

being a member of a youthful “yegg gang” whose operations extended for San

Francisco, California to Ogden, Utah by riding the freight box cars along the

railroad route.

The term Yegg or Yeggman originated

in New York City and was a Yiddish word for a “clever thief. The word came to

be applied to hoboes who originally were beggars but later became thieves. A

Utah newspaper account described a Yeggman or hobo “as a rule” to be “a

wanderer, along out of the way paths and crossroad, camping in unfrequented

woods and swinging on and off of freight and passenger trains at sidings and

water tanks along the principal lines of railways. This class of criminals

operates singularly, in threes, fours or even in greater numbers” however ‘Four

men are usually selected out of some yegg or hobo camp.”

These hoboes or Yeggmen were said

to have caused the Southern Pacific company “considerable trouble by numerous

depredations along the line between Ogden and Oakland.”

From San Francisco Sullivan made

his way to Utah where he got into some trouble in 1901 when he was 22 years

old. He and a man named John Moffatt were arrested on a charge of

“drunkenness.” After appearing in a Brigham City Court, they “were escorted to

the county jail to serve twenty days.”

After spending time in a Brigham

County jail, Joe Sullivan led the life of a “tramp vagabond” living in hobo

camps along Ogden and Weber Rivers and coming into Ogden to primarily beg for

money. In 1902 Sullivan was arrested again and charged with “mendicancy”, a

legal term used to mean the practice of begging. Sullivan pleaded guilty to the

charge as that he had been begging in the streets of Ogden and had even knocked

a man down who refused to give him money. He “received the limit- a sentence of

30 days on the rock pile.”

In July 1903 Sullivan was listed as

one of several “hoboes” rounded up by the Ogden River and told to leave town.

He was found next in the railroad town of Terrace, Utah in west-central Box

Elder County. Terrace is now a ghost town in the Great Salt Lake Desert United

States but was once an important operation base for the Southern Pacific

railroad.

There he was using the alias Joe

Harrington and was in the company of Ed Walker, Jack McMann, and a young 25 year old man

named John Furey but nicknamed “Dago.” Furey may have been of Italian or

Spanish descent as "dago" is a derisive term for people of that

ethnicity. Under the name Joseph Harrington, Sullivan considered the ring

leader of this gang of hoboes as he may have been the oldest at the age of 24.

In the middle of August the Box

County Sheriff was summoned to Terrace because of the report of a “tramp” being

shot and robbed. In some reports he was simply named as a laborer or a

transient. The initial story was the John Furey, in some accounts named “John

Shurey,” was robbed of $75 in gold and $12 in silver and the shot in the leg

below the knee. It would have been suspicious that a so called tramp would

possess that much currency.

“John Furey, a transient, was shot

at Terrace and robbed of over $80. Shooting took place in the railroad yards

and believed to have been done by three hobos with whom he had been in company

that day. He was shot in the knee and fainted from the pain and was robbed in

that condition and therefore unable to say who shot and robbed him.”

The story should have been suspect

when it was revealed that Furey had been seen in the company of the hobos said

to have robbed him and that he could not identify his assailants even though

“Harrington,” Walker, and McMann were captured after the shooting by rail yard

workers and held in a box car until the Box County sheriff arrived.

Furey was transported to a hospital

in Brigham City to have his leg treated

while the three men, locked in the box car, were transported to the

Brigham County jail. This was not what was expected by the youthful hobos. The

story of Furey being robbed and shot as it turned out was fabricated in order

for Furey to receive medical treatment when he had accidently shot himself in

the leg while in the railroad yards.

“It now appears they were all in

the same gang and while waiting for a freight train at Terrace on which they

intended to ride to Ogden, Furey accidently shot himself. In order to get

sympathy and medical attention. It was decided by the gang that the wounded man

should tell the story of the shooting and robbery. This part worked all right

but the others did not calculate on being arrested themselves for the crime.”

In the Brigham City court room

Furey would not testify against his compatriots who were charged with assault

and because of insufficient evidence, “Harrington,” McMann, and Walker were

released after the charges dropped. Sullivan must have gone back to Ogden along

with John Furey, Ed Walker, and Ed McCann as they began a crime spree there.

In September 1903, Joseph Sullivan

along with an unnamed partner began begging again in Ogden, this time armed

with a stolen pistol. He encountered three “Baggage men,” railroad employees in

charge of the checked baggage of passengers. The trio were walking along the

Twenty-Fifth street and Sullivan accosted them for money. When the men refused

him, Sullivan “whipped out a revolver and flourished it in a threatening

manner.” The baggage men however subdued Sullivan and a police officer was

summoned to arrest him. Sullivan was charged with “assault with a deadly

weapon,” against the three “Baggage men,” named Renford Hart, Joseph Hall, and

Henry McLaughlin.

Joseph Sullivan was arraigned in

the Ogden Municipal court and his bond was set by the court at $1000 which of

course he could not raise so he remained in jail until his trial in October. It

was reported by all of the Ogden law officers that Sullivan was “considered one

of the worst crooks the jail has held for some time.”

While Joseph Sullivan was in the Ogden jail, a Box Elder county

Sheriff was visiting and he recognized

Sullivan, as the same man he had arrested in Terrace, Utah calling himself

Joseph Harrington. When the Sheriff “walked into the jail corridor, Sullivan

spoke to him, and the Sheriff said, “Hello Harington,” and Sullivan greeted him

in return.

In early October, Sullivan finally

appeared in the district court before Judge Henry H. Rolapp charged with

assault with a deadly weapon. As that he plead not guilty, his case was heard

before a jury which listened to the testimony of a number of witnesses

including that of Hart, J Hall, and McLaughlin, the three baggagemen who

Sullivan attempted to hold-up on September 6th at the corner of Twenty Fifth

street and Lincoln avenue.

The prosecutor remarked “It was

shown that Sullivan stopped the men and asked them for some money which the men

said they did not have any, he then drew a revolver and flourished it around

saying he was going to have some money anyhow.”

After the case went to the jury,

they brought in a verdict of guilty. Sullivan was the taken back to his jail

cell to await his sentence which was to be passed the next morning. Unknown to

the jailer, Sullivan had been working on an escape plan by sawing through the

iron bars and fashioning a key to unlock his cell.

When Sullivan was arrested in Ogden

newspapers reported that he had been the first prisoner in the new Ogden jail

and was the first person to make an attempt to escape from it.

While during the month he was in

the jail waiting for his trial, Sullivan managed to acquire three long brass

printer’s rulers. After securing the ruler, he “kept his eye upon the jailers

and when they locked and unlocked the cell doors, he carefully studied the key

used. Sullivan made two keys “created only from him seeing the jail key that

was kept in the hand of the sheriff or the jailor when Sullivan’s meals were

brought to him.” In this way he gained a

general idea of the size of the key and the manner in which it had been made.”

Sullivan filed one of the rulers as nearly to the

proportion s of what he had seen, afterwards “smeared soap upon the end of the

ruler and reaching through the bars of his cell inserted the soap covered end

into the lock. When he withdrew the ruler, it bore the marks of the interior of

the lock.

His first key was not a success but

was “of a great assistance to him making his second.” Sullivan’s second key was

able to unlock the cell door. Watching for an opportunity, he opened the cell

door and gained the jail corridor where it was necessary for him to “file

through some steel bars before gaining liberty.” He had nearly sawed through

the bars of his widow when he was discovered.

That night, after his conviction

and while waiting for his sentencing, Sullivan was back in his jail cell, a

deputy sheriff, making his midnight rounds, noticed that Sullivan’s cell was

unlocked and the widow bars had been cut . He confronted Sullivan who then

admitted hiding the tools he had used in his jail toilet. He handed the key he

made to the guard and when tried the key was found to work perfectly.

The sheriff was dumbfounded by

Sullivan’s skill and even informed him that the Yale Lock manufacturer

reportedly had offered $5000 to anyone “who could make a key that would unlock

the jail locks without having a model to go by.” Sullivan laughed and

reportedly said, “Why any baby could unlock ‘em.”

Sullivan later even offered to show

the committee, appointed to investigate the attempted jail break, some

“valuable pointers as to the flaws in the jail bars and in the cell door

locks,” hoping the information might reduce his sentence. It didn’t but so

remarkable was his skill in fashioning the key that he was called “one of the

cleverest lock pickers the country has known for a long time.” That key and several others made by the

ex-convict became the possession of Salt Lake Police Chief Thomas Pitt in 1908 as proof of Sullivan’s ability to

mastermind an escape .

After “his work was discovered,”

Sullivan had an “Oregon boot” placed on his ankle and shackled with handcuffs.

An Oregon Boot was a heavy iron shackle place around the ankle which made it

difficult and painful to walk. It was reported that Sullivan walked back to his

cell “like one used to carrying the iron boot.”

So concerned over Sullivan’s escape

abilities, Ogden authorities sent his photograph out to other law jurisdictions

to be placed in the “Rogue Gallery” so

as to have his likeness on file.

The next day, Judge Rolapp, having

been made aware of Sullivan’s escape attempt, said, upon pronouncing

sentencing, that he had at first

considered and thought Sullivan simply “a drunken tramp” but “since his attempt

to break jail last night the court was more than convinced that he was a

hardened criminal.” The court sentenced him to

three years in the state prison for the charge of assault and an

additional two years for attempted escape.

While Sullivan was languishing in

an Ogden jail cell waiting to be transferred to the state penitentiary in Sugar

House, his pals Ed Walker and Jack McCann were arrested at the end of September

1903 for stealing a watch from a shoemaker shop. They were described in reports

as “youthful desperadoes” and “apparently under 25 year of age.” They were arrested

at the Hot Springs in North Ogden and sentenced to sixty days in the county

jail.

Chapter Four

John Joseph Furey [1877-1922]

While Sullivan was being

incarcerated in the Sugar House Penitentiary in October 1903, John Furey was

involved in the robbing of the Ogden Zang Saloon. While some of the hold-up men

were caught, Furey managed to escape to California where in November 1903 he

was involved in an incident in Oakland. There he was shot in the arm and first

taken to the Oakland Receiving Hospital. To show that he was not a vagrant,

Furey gave to the police as his occupation that of a “boiler maker helper” and

his address was 312 York Street in San Francisco’s Mission District where his

mother “Mrs. Wieland” lived.

When questioned by the police about

his being shot, he told a story that he had been heading back to San Francisco from Los

Angeles where he had tried to find work. He explained that he and a friend,

named Alexander Kinney, were riding on the top of a freight train box car

heading into Oakland when at the Sixteenth Street depot rail road yard he was

shot in the arm by another man who had been hitching a ride on the same train.

He claimed he did not know why he was shot and who the man was that shot him at

close range was. The “unexplained shooting” of Furey caused the “rounding up”

by the police of “tramps at the yards in Oakland.”

“When day dawned, nine hobos were

taken in the dragnet” but Furey was “unable to identify his assailant” among

them. More than likely, Furey was unwilling to identify the man who shot him.

The police were skeptical of Furey inability to help them find his assailant;

therefore the officers were “satisfied” that Furey was actually shot by another

member of the gang of hobos who had come in with him.

By some means or another, Furey

learned that a detective from Salt Lake City was looking for him and “he

quietly disappeared from the hospital.” He must have made another foray into

Utah as that in December 1903, while using the alias of “John Sullivan”, Furey

returned to Ogden during Christmas week.

There his gang was breaking into

freight box cars in the Ogden rail yards to steal merchandize when they were

discovered by two Southern Pacific Railroad special agents. A gun battle

insured and the special agents were shot and killed.

A Southern Pacific Detective named

William Sullivan was assigned to the case and traced Furey “an alleged

desperate criminal” back to San Francisco where Sullivan contacted railroad

agents there to be on the lookout for him.

In March 1904 John Furey still

using the alias Sullivan “was arrested at the home of his parents on York

street in San Francisco.” Southern Pacific Secret Service Agents had been

tracking him as that he “was the leader

of a gang of vicious robbers operating in and around Ogden Utah.” Furey was also

accused of being the head of a “Yegg gang” of 25 men who were committing

robberies in Utah and train hold-ups in Nevada. Besides common robbery, Furey’s

gang gave the railroad company a “great deal of trouble by breaking into

Southern Pacific freight cars and carrying off valuable merchandize.”

However John Furey was mainly

wanted by Ogden authorities for his involvement in the Zang Saloon robbery and

for the murder of Roy Wells, a young man found on the banks of the Weber River

with a bullet hole in his head. Furey was implicated in the murder of Wells as

Wells was believed to have been murdered for having given police officers

information about the Zang Saloon Robbery. Furey denied having anything to do

with the killing.

Furey was extradited to Utah and

convicted in April for robbery. He was sentenced to the state prison where he

served time along with Joseph Sullivan who was also incarcerated there.

Chapter Five

The Most Dangerous Man in Prison

When Sullivan was sent to the Utah

state penitentiary at the age of 24 years, he immediately won the reputation of

being one of the most dangerous men in the prison. In the Utah State

Penitentiary Joseph Sullivan was not a “model prisoner” as per a litany of

offenses committed by him that were kept on file.

In 1904 he was “found with a knife

in his possession”, “was punished for violating the rules continually,” “making

unnecessary noise in cell after lock up”, “found in the hospital making keys to

get poison which he was going to use on the guards”, and “punished for

neglecting his work and for violation of rules, for stealing food, and abusive

language.”

In 1905 Sullivan seemed to have

settled down and his only infraction was again being caught with “keys in his

possession” It seems his most serious infraction was on 25 September 1906 when

he assaulted another inmate with a two inch pocket knife.

Although Joe Sullivan seemed to

value the “evil reputation” he had won, his acts of rebellion against prison

rule were due to a desire to “excite the admiration and wonder of his fellow

convicts.” He was “savage and brutal to the men who imprisoned him, and they

“feared him and while taking a lively interest in his movements were careful to

keep out of his way as much as possible.”

In September 1906 Joseph Sullivan

made the news again by stabbing two prison inmates. It seems that 25 year old

William Taylor Lewis [1881-1961] was the main target of the assault and as the

“corridor was crowded and in the mix up another inmate” named Newton was

“slightly wounded in the arm by one of Sullivan’s wild stabs.”

The

assault on Lewis occurred in the washroom just before supper and was said to

have been entirely unprovoked.” Sullivan was placed in solitary confinement for

the attack. An investigation held stated that Sullivan was entirely to blame

and reported that he and the Newton the bystander who was also stabbed belonged

to the “hobo” class and were bent on making trouble for Lewis “whose

“ante-penitentiary associations were of a different sort.”

Why Sullivan lashed out William

Taylor Lewis [1881-1961] is not indicated in the newspaper accounts but

probably had to do with Taylor being a fundamentalist Mormon. Taylor had only

just been sentenced to prison on September 13, two weeks before the attack so

the assault was not due to a long standing feud

between them.

Taylor was from Richmond, Cache

County, Utah and was referred to as a “young man of good family connections.”

His father was a Mormon polygamist siring 22 children and Taylor also practiced

plural marriage. Lewis was convicted on a felony charge for committing adultery

with a young woman named Edna Phillips in April 1906 who he probably seduced

into polygamy. In July she was the one who swore out a complaint against him

when he was charged with adultery and unlawful cohabitation.

“Cache Man Is Arrested- William T

Lewis, Formerly of Salt Lake, Charged with Criminal Offence- William T Lewis,

formerly of this city, for an offense committed with Edna Phillips, a young

Salt Lake Woman. Lewis is married and took Miss Phillips to his home, it is

said, under the promise of marriage, even if it should be necessary for him to

take her to Mexico to have the ceremony solemnized. Lewis is a grandson of the

late W.H. Lewis, president of Benson Stake. He is ill with spotted fever.

[Spinal meningitis]”

A newspaper reported of the affair.

“The case is unusually revolting, criminal relations have been maintained

continuously since in Salt Lake, San Francisco and other places, the guilty

couple flaunting their adulterous life before the very eyes of Lewis’ wife.”

Taylor had taken Phillips to San

Francisco and was there at the time of the great 1906 earthquake and then

returned to Utah afterwards. Taylor was sentenced to serve one year in prison

but was pardoned nine months later in June 1907 after a letter writing campaign

by Logan people.

Due to the assault on Lewis, Joseph

Sullivan forfeited his credit for good behavior which would have reduced his

five year sentences by three months. Because of his violent and rebellious

conduct, Sullivan lost nine months and 11 days of “good time” which was the

usual deduction from a five-year sentence.

Because of his revolts against the

authority of the guards, Sullivan spent much of his time in solitary

confinement and had lost all of the “good time” allowed to convicts who display

a “disposition to reform, or, at least in inclination to serve out their

sentence quietly and submissively.” Had he obeyed the prison rules and

refrained from his frequent revolts he would have been released from prison in

February, 1907. As it was “he did not doff the stripes” until when he “came

forth branded as a dangerous man and his movements were watched.”

Joe Sullivan achieved the

reputation of being “one of the most desperate unruly convicts in the Utah

State Penitentiary. Many of convicts

“brutal and harden as most of them were,” became afraid of Sullivan and during

the entire time of his confinement none dared cross him in anything.”

While being confined to solitary

confinement, Joseph Sullivan, along with thirteen other prisoners confined for

serious infractions, was involved in a riotous protest against prison rules and

was “severely punished.” The offenders who had been placed in solitary

confinement were mostly “housebreakers and highway robbers, but they were

considered “the most troublesome thugs with which the prison authorities have

to deal. They rejoice in the distinction of being hardened bad men.”

Newspaper headlines from the

November 1906 reporting on a “prisoner mutiny” read “Prison Convicts In

Insurrection-Drastic Measures Necessary to Quell Uprising in Penitentiary-

Punish Fourteen leaders- Governor Cutler gives the rebels cold comfort.”

Joseph Sullivan, as one of

“fourteen tough convicts” was punished with the others for the “offense of

creating a disturbance and making themselves generally obnoxious.” While he and

the others had been in solitary confinement, they “indulged in profanity and

boisterous conduct.” The men “hooted and yelled” and stamped “on the metal

floors with their heavy shoes.” They did a “War dance, pounded on bars with tin

bucket covers,” and gave out “blood curdling yells.”

The fifty-three year old Prison

Warden, Arthur Pratt, decided that stern measures were necessary to

|

| Arthur Pratt |

control the men and teach them a lesson. Arthur Pratt, [1853-1919] the son of Mormon Apostle Orson Pratt, had been appointed warden just two and half year before when he now had to deal with this uprising. Actually it was his second time as head of the prison as that he had been appointed warden of Utah Territorial Penitentiary in 1888 and served for a year. During his second role he served as warden for 13 years and was head of the prison when labor organizer Joe Hill was executed in 1915.

Warden Pratt ordered the frustrated prison guards to seized eight of the worst offenders and marched them to a gloomy building called “The Tombs,” so named because of the executions which had occurred there. “The place was regarded by the prisoners with superstitious dread.”

At the Tombs, the prisoners were

stripped of “the clothing from their bodies” then they were “trussed up in two

stone cells with arms outstretched in opposite directions at full length and

hands manacled to rings in the wall.” The men remained standing in that

position for twenty-two hours with only a brief interval “when the convicts

were given a slice of dry bread and a cup of water.” This punishment was meant

to bring the men “into a spirit of obedience to prison rules.”

The “mutinous offenders” were

visited by prison guards every half hour, after being trussed, to check on

their conditions. On those occasions the guards were met with a “volley of

dreadful curses and obscene abuse.” It was noted that the convicts “had a

disposition not to be conquered. They profane at nearly every breath and

threaten dire vengeance upon the heads of the officers for the punishment

inflicted.”

After

being chained for twenty-two hours, and fearing “physical collapse,” the

prisoners were released at night and “ thrust into absolutely bare cells” where

they laid naked and “groaned on the bare floor, with tongues parched and joints

wracked by pain.”

The next day the men underwent a

repetition of the “tombs discipline” and were to stay there until it was

“apparent that the insurgents have had enough to insure obedience.”

The Board of Corrections, along with Governor John C Cutler, [1848-1926] met at the Sugar

|

| Gov. J C Cutler |

House prison during the chaining of the inmates to the Tombs stone walls. They went to witness the inmates undergoing their punishment. Governor Cutler, not the least bit sympathetic, was said to have “read the riot act to them” and made it plain that Warden Pratt had “his full support in maintaining discipline.”

Warden Arthur Pratt explained to

reporters why he resorted to this Draconian form of punishment. He said, “I am

placed here to take care of these men. I must not let them get away, nor must I

allow them to do bodily harm to each other, and if our rules were as strict as

the rules in other prisons, I believe that I would not have so much trouble as

I am having at the present time.” He noted that “whipping posts” were not allowed

under Utah law and reasoned saying, “The only punishment that I am subjecting

the men to, is to chain their hands against a cement wall where it will be

impossible for them to sit down.” He also said he feared that a rebellion at

the prison could spill over to the dining room setting “where two hundred

inmates were bunched together at meal time and he feared riot there would mean

a loss of life.”

A year after the “insurrection”

Sullivan left the prison on 9 December 1907. He was 28 years old and “was in an ugly mood”. Both the Salt Lake

City police and County sheriff offices were warned “that a particularly

dangerous man was about to be turned out of the penitentiary.”

The prison guards who had watched

over Sullivan for the term of his incarnation felt convinced that he would

return to his life of crime. “Sullivan entered the prison a wolf of society and

came out more wolfish than before.”

Chapter Six

John William Owen [1873-1942]

John W. Owen was

born according to birth records 3 January 1873 in the town of Canton, Starke

County, Ohio, although he claimed the date 22 January 1872 and 22 January 1874

when he applied for Social Security as an adult. His father, who was a brick

mason, died when he was 9 years old leaving his widow to raise five minor

children. He was the middle child among two older brothers, and a younger

sister and brother. His mother never remarried so John Owen would have been

raised in near poverty.

While there is no physical

description of John Owen, a military draft record showed that his younger brother

had brown eyes and black hair. Physically Owen was about 2 inches shorter than

either Joseph Sullivan or Joe Garcia who were about the same size. He was said

to be 5 feet 7 ¼ inches and a reporter described him as “a dark, insignificant

looking man, with an impudent, evil face.”

While there was little information

about his physical appearance, his character was impugned in most accounts

written about him. He was called a “jackal” and another reporter described him

as a “sulking cowardly creature evil at heart.” Still another wrote that Owen

was “a cruel, wicked, and criminal man,” and “Owen lacks every element of

manhood.”

In October 1897 a grand jury in

Canton, Ohio indicted 24-year-old John Owen for burglary, robbery, and larceny.

He pled not guilty but was convicted in November and sentenced to three years

in the Ohio State Penitentiary located in Columbus, Ohio. As that he was

not located in the 1900 federal census as being an inmate of the prison, he may

have been paroled by then.

Owen left Canton, Ohio behind and

went west. His older brother had worked as a conductor for a railroad and he

probably went west to work where no one would know his criminal background.

When Owen came out west, he stated

he found work upon the railroads as a “brakeman.” As a brakeman, he was a

member of railroad train crew. He was employed by the Western Pacific Railway

Company, which was formed in 1903. While working for the Western Pacific, he

lost his three fingers on his right hand on 18 Jan 1905. After his accident he

no longer could work as a brakeman.

Owen then found work as

“switchman,” operating the “track switches” for the San Pedro, Los Angeles, and

Salt Lake Railroad’s “Salt Lake Route.” As part of his job he was responsible

to inspecting important parts of the trains and attaching and detaching freight

cars.

It was reported that in this

position he “levied tribute upon the tramps and impecunious workmen who rode

from place to place upon the freight trains.” He was said to have forced

“wretched wanderers to yield to his portions of their meager sums which stood

between them and starvation. His spirit fed upon the submission of the poor

outcast whom he bullied and terrorized.”

Owen claimed he came up to Salt

Lake from “Lynn, Utah” after he lost his position with the “Salt Lake Route.”

However Lynn is in Box Elder County, Utah located in the northwestern corner of

the state, close to Utah's border with Idaho. He actually probably came from

Lynndyl 120 miles to the south in Millard County. Lynndyl was a railroad town

and the location of a fork in the San Pedro Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad

where one branch proceeded to Provo “via Nephi and Santaquin and the other to

Salt Lake City via Tooele.”

Owen stated that he had spent all

his money when he met Joseph Sullivan in December 1907, soon after the Sugar

House convict was release from prison. As that most of the information Owen

offered up to law officers was self-serving, it is hard to rely on his version

of his coming to Salt Lake. He claimed he was in Salt Lake only four days

before the Albany Saloon robbery in the early hours of December 14, but Salt

Lake detectives did “not give much weight to that story” as he seemed to have

been an associate of Joe Garcia, “one of the most dangerous criminals that ever

invaded Salt Lake.” They could “not believe he could have won the confidence of

the wily half breed in so short a time.”

Also a daytime Albany Saloon

bartender believed that he saw Owen in the bar a good week before the robbery.

Whatever actually was the case when he came to Salt Lake City, he “immediately

fell in with a gang of criminals” and within days Owen was used by Garcia “as a

scout or spy to study the opportunities offered for robbing houses.”

PART TWO

Chapter Seven

Paroled

On Monday December 9, Joseph Sullivan

was released from the Sugar House state penitentiary at 9 in the morning. He

was given a gray suit by the prison and $27. He then took a street car down

town and sometime that afternoon he bought a .38 caliber Smith and Wesson

revolver “paying $3 for it.” He was being closely watched by law officers as

that he had won the reputation of being the “most dangerous criminal in

prison.”

The next day Tuesday December 10,

John Owen said that when he arrived in Salt Lake City he was “begging upon the

street being hungry and without money. He accosted Sullivan for the price of a

meal and Sullivan gave him 15 cents. Two or three policemen, watching the

transaction, ordered Owen to leave Salt Lake threatening him to arrest him for

vagrancy.

After the police departed, Sullivan

walked away with Owen and told him “not to take any notice of the officers.”

Instead Sullivan “took his newly found friend” to various saloons” namely the

Continental saloon of the Southwest corner of West Temple and First South and

the Jubilee at 26 Commercial Street,

“where plans for obtaining money by robbery were incubated.”

The saloons of Salt Lake City were

seen as moral cesspools of alcoholism, illegal gambling and of course

prostitution A reporter described a visit to Commercial Street and the

surrounding district in August 1907 writing; “Women old, fat, broken down hags,

standing brazenly at the bars leering in time to the supposed music of an

orchestra or mechanical played piano or soliciting trade in the wine rooms in

the rear were common in almost every saloon.”

Salt Lake City ordinances ordered

these “dives” emptied of women between 7 in the evening until 7 in the morning

however the law was generally not enforced and the wine rooms in the rear of

the saloons, partitioned off private spaces, were used for intrigue and sex.

The same writer described Salt Lake

City Commercial street saloons as “dirty and disgusting premises” and

especially suggested that the “wine rooms” were particularly dens of iniquity.

In most of the downtown and Commercial street saloons had cubicles in the rear of the bar, forming small booths

often called “wine room,” in which all sorts of disreputable characters could

congregate “safe from the scrutiny of patrons of the bar rooms and from the

streets. These areas were known to police as “retreats for men and women of

questionable character.

A newspaper reporter described such

wines rooms as “fitted out with tables chairs and a couch, the purpose of which

is only too apparent. Apparatus for the whole gamut of bestiality and crime, in

its lowest form, are there with them who lend body and soul to such horrible

practices plying their trade.”

The Saloon’s “wine rooms” were the

cause of “a great deal of annoyance to the police.” Drunken and “horny” men

frequented these booths to meet “disputable women” who would often be found in

them; but as often as not, crooks robbed

the inebriated in these secreted places.

The Jubilee Saloon was particular

portrayed as a dismal place. An old red sign hung above the entrance to the

bar, where men entered who were “strange wayfarers who floated into Salt Lake

and then out again; all the odds and ends of western humanity, some merely hard

drinkers, who were wifeless, childless, homeless, without hope and ambition,

others with shifty eyes and pasts which they dared not bare to the gaze of the

world.” Certainly, Owen and Sullivan were a little of both.

These two favorite “haunts” of Sullivan and Owen

were probably chosen because Owen knew the bartenders at each place. Both the

Continental Saloon and the Jubilee also contained back rooms used where

Sullivan and Owen could plot and plan without being noticed or seen.

Tip Belcher was the night bartender

at the Jubilee and James “Jim” L McGivern was a bartender at the Continental.

Both these men had rooms at old Kimball house on North Main street. Belcher was

also providing a hiding place for Joe Garcia of which undoubtedly McGivern

knew.

Chapter Eight

Rolling a Drunk

In the late afternoon, prison guard

William Irving was ordered by Warden Arthur Pratt to go into town to check up

on Joe Sullivan and see what he was doing, in the company of Henry C Taggart,

another prison guard. Between 5 and 6 in the evening, Irving located Sullivan

who was still wearing his gray suit. He was in the Continental Saloon in the

company of a man they did not recognize. Sullivan introduced Owen by the name

of “Johnson” to the guards.

Irving was suspicious of the pair and he

warned Sullivan “not to get into trouble.” Sullivan just laughed and said to

Irving “If you bulls want to take me for anything you will get a fight;” bull

being a prison term for a guard.

At the Continental saloon, Sullivan

may have suggested to Owen that they could “roll a drunk” to make some easy

cash. A day laborer Swede named Pete Peterson

was there completely intoxicated in one of wine rooms, partitioned off

from view from the rest of the bar room.

Pete Peterson had been drinking in

the saloon, “considerably,” for the past two of three days it was reported.

During that time he was “singing and dancing for the curious customer” and so

intoxicated he could hardly walk.

In the evening Peterson was last

seen by customers walking towards the rear of the saloon where the wine rooms

were located after drinking another glass of beer. Passing through, he went

outside the rear of the saloon into a little passage way where Sullivan seized

“the drunken man around the neck and although the man was powerless to resist,

he beat him on the head with the butt of his revolver.”

However as he struck Peterson the

weapon accidently discharged which frightening the two hold-up men, causing

Sullivan to release the Swede and he and Owen fled in panic.

At the same time it was reported to

the police headquarters that “three shots were heard in the vicinity of the

“old Continental barroom” at First South and West Temple. “With clanging of the

bell and the urging of horses the patrol wagon with officers on board made a

rapid run to the scene of the allege shooting.”

After a stranger had told him of a

shooting, John Ingram, a livery stable laborer, stepped out of the back door of

the Continental saloon and found Peterson in a little passageway stretched upon

the ground. Peterson was unconscious and bleeding from wounds upon his head.

Ingram then carried the Swede inside.

“For a time there was great

excitement about the saloon” as people at first supposed that Peterson had been

attacked and rob or even had tried to commit suicide.

The police who were in the area

looking for some shooter were summoned. They questioned John Seren, the

saloon’s proprietor, and the bartender both who claimed they hadn’t heard

any shots. There was a large crowd in

the bar at the time, but there were no music or loud talk according to the

police.

Pete Peterson was taken to the

emergency hospital where it was stated that his head injury was not from a

gunshot wound but “had apparently been caused by a fall.”

Peterson was unable to make a

statement and in his pocket the police found $1.80. The police were informed

earlier that when the Swede had entered the saloon he only had $2 so robbery

was ruled out for his injury. The police thus “were not disposed to credit to

the general belief that he had been knocked down by thieves.”

The police assumed that because

Peterson was so inebriated, he simply had fallen down and injured himself.

After his wounds were treated, as that Peterson was clearly “under the

influence of liquor,” he was arrested and charged with drunkenness. After

sobering up in the “drunk tank,” however Peterson then told the police that he

had been attacked and an attempt to rob him was made by two men.

After the revolver discharged,

Sullivan and Owen quickly made their way back to Commercial street. Two Salt

Lake police detectives who had been watching out for Sullivan for some time

spotted him with Owen, who was unknown to them. They were seen rushing about on

Commercial Street and after having heard shots a block away, the police

detectives suspected that Sullivan might have shot someone in an attempt at

highway robbery. They suspected he was hurrying into the heart of the city to

hide himself in the crowd.

On Commercial Street, the two

police detectives stopped the men as suspicious characters and as the

detectives could smell burnt gun powder on Sullivan, they frisked the pair.

Sullivan and Owen had loaded concealed weapons in their pockets. The handle of

the weapon belonging to Sullivan was covered with blood and one of the

cartridges showed it “had been discharged within a short time before they were

taken into custody.”

When asked to explain why the men

carried loaded revolvers and how the blood came to be on the handle of

Sullivan’s gun, both Sullivan and Owen refused to talk. “They had no

explanation whatever to make.” The detectives then took Sullivan and Owen to

police headquarters, just about a half hour after Peterson had been found

wounded.

The arrest of Sullivan and Owens

was actually part of a “round trip up of numerous vags and loafers” that night

on Commercial Street as that the police had been investigating a series of hold-up

men “who have been operating in Salt Lake for some time.” Still the police

suspected that Sullivan and Owen had committed some crime and had hurried to

Commercial Street to thinking they might “hide in one of the cheap lodging

houses there.”

Charles Ford, one of the new

policemen appointed on Tuesday, was patrolling his beat in Greek Town.

Chapter Nine

Sullivan and Owen Arrested

As that the police department had

been warned about Joe Sullivan’s release from prison, Chief of Police Thomas D

Pitt, after being informed of his arrest, told newspaper reporters working the

“Police Beat” why Sullivan was taken into custody. He said that there was

“reason to believe Sullivan has been connected with some of the recent thefts

and robberies” and that the reason for the roundup of Salt Lake’s vagrants was

that “last night three pistol shots were heard in the vicinity of First South

and West Temple and the police at once made an investigation.”

Sullivan and Owen were interrogated

by the police “up to an early hour” on December 11 Wednesday morning. The

police however “were not able to learn of any shooting affair with which they

could connect Sullivan,” but suspected he had assaulted Pete Peterson.

During a police lineup at

headquarters, the Swede was not able to identify Sullivan and Owen as his

assailants, however when others in the Continental Saloon were questioned

customers said the pair had been seen “hanging about.”

As that Sullivan and Owen were

unable to post bail, they were lodged in the city jail on Wednesday remained there waiting

a hearing on Friday.

That Friday December 13, in the

morning, Joseph Sullivan and John Owen appeared before Police Court Judge C.B .

Diehl. The police however failed to secure sufficient evidence to connect them

to the assault on Peter Peterson, and they were released. Nevertheless,

Sullivan and Owen were given by the Judge Diehl “two hours in which to leave

town” as they were suspicious characters.

It was a common practice to allow

vagrants to leave the city and they were

often referred to as “floaters.” Instead

of leveling a fine or incarcerating them, these vagrants were allowed to

“float” out of town. Sullivan and Owen were such “floaters” however they did

not leave Salt Lake City.

Police Detective Richard “Dick” L

Shannon released Sullivan and told him he was an “undesirable citizen. The

police confiscated his revolver but returned $4 to Sullivan which was all he

had left of the $27 he had when he left prison.

After leaving jail, the Sullivan

and Owen went to the Oregon Short Line

depot to inquire when the next train was going south on the San Pedro Railroad.

They were told that the Los Angeles limited would not leave until eleven

o’clock that night. Sullivan and Owen then walked back towards the center of

town stopping at the Sindar’s Saloon at 51 West First South Street “for a few

glasses of beer.”

As “floaters,” Joseph Sullivan and

John Owen were “trailed by police detectives to make sure they were leaving

town. The detectives followed the two men during the afternoon into the night

“as they skulked from saloon to saloon” until their track was finally lost.

After leaving the Sindar saloon,

the men went to the old St. Mary’s Catholic Church at 50 South Second East

where they met up with “short and stout and round about” Father W. K. Ryan.

Sullivan went to see Father Ryan to ask for help getting to Garfield and the

priest gave him fifty cents. Afterwards the pair went back to Sindar’s to drink

some more.

In the late afternoon they

“strolled to the Albany Saloon” at 597 [579] West Second South where John Owen

“sold a ring to the day bartender.” With the money from the sale of the ring,

they walked up to the Hurry Back Saloon at 502 West First South. After a few

beers there, the men then went to The Court

Saloon at third South and State Street where Sullivan encounter a recently

release fellow prison inmate named “Doc Gibson,” with whom Sullivan had been

acquainted in prison .

John Owen and Joe Sullivan were

last seen by the police detectives “late on Friday night wandering on South

State Street.” They had until then dodged through the city to “escape vigilance

of the police and deputy sheriffs.”

Doc Gibson was an ex-convict from

the Idaho State prison, who had arrived in Salt lake City in November 1906. His

real name was probably “Henry” or Harry L Gibson but he had also used many

aliases like “H.D. Kendall” and “Coleman’ as well as “a few more.”

Shortly after arriving in Salt Lake

City, Doc Gibson was arrested for passing a forged $30 check at the Lyric Bar

at 331 South State Street. He was convicted on the forgery charge and sent to

the Sugar House Penitentiary in February 1907. He was sentenced for only a year

because he had made “restitution” before being arrested and so he was “let off

with a light sentence.” He did not serve his full sentence but was paroled just

a months prior to when Jose Sullivan was release from prison.

After leaving the Court Saloon,

Gibson, Owen, and Sullivan walked back to the Continental Saloon about eight

o’clock in the evening. There is the bartender James “Jim” McGivern, said to

John Owen that “a party was here asking

for you and Sullivan and called himself Chink.” Joe Garcia who was known as

“Chink” evidently must have known John Owen if he was asking for him. Sullivan

and Owen had been in jail since Tuesday night therefore Owen most likely had to

have known Garcia prior to when he said he came into town on the day he said he

met Sullivan.

If Owen knew Joe Garcia, then he

may have known also that Tip Belcher, the Jubilee bartender, was harboring

Garcia and would have known how to reach him. After leaving the Continental the

men walked back to the Jubilee Saloon where Belcher was bartending. Evidently

Joe Sullivan did not know of the connection between the bartender and Garcia

for he asked Belcher if he knew “Chink.”

Owen and Sullivan told Belcher that

they were about to leave town and they wanted to know if Garcia wanted to leave

town with them. This was another indication that Owen was acquainted with

Garcia more than he admitted. Belcher told the pair that he thought Garcia

might want to get out of town. Sometime later Belcher contacted Garcia and made

an appointment for the two men to meet up with Garcia in front of the

Continental saloon at midnight.

Chapter Ten

Garcia Meets Sullivan an Owen

Tip Belcher did not know Sullivan all that well, as that he later testified that he could not be certain that he had ever seen Sullivan before December 13 but believed that he had seen a man with John Owen that night who “represent himself as Joe Sullivan”. Belcher said that Sullivan and Owen were in the Jubilee drinking about ten o’clock that night.

Doc Gibson showed up at the Jubilee

Saloon about that time and he went with Joe Sullivan into a rear “wine

room.” Alone with Sullivan, Doc Gibson

listened to Sullivan’s need for cash relating as that he had been ordered out

of town. Sullivan believed that since Gibson was an ex-convict that he was

trust worthy. He had no idea that Gibson was actually acting as an informant or

“stool pigeon” for the sheriff office and would later report what he had heard

of Sullivan’s plans to hold-up a saloon. Gibson told Sheriff Frank Emery that Sullivan “talked freely” of his plans of

holding up a saloon to get the money necessary in order to leave the city.

As Sullivan and Owen were low on

funds from drinking all day, Doc Gibson

suggested that they come to where

he was lodging, to pass the time and have a pitcher of beer while waiting for

“Chink” to show up. They agreed and stayed in Gibson’s room drinking until

nearly 11:30, when Owen and Sullivan to return to the Jubilee saloon.

There they began drinking again in

one of the back wine rooms as to be out of sight. Shortly Tip Belcher came in and told the two men that

Joe Garcia was waiting for them over at the Continental Saloon. Sullivan and Owen

got up and left to meet up with Garcia, evidently someone Owen would have

recognized.

At the Continental, Jim McGivern

“the bartender” said he had seen Owen and Sullivan in his place several times

during the evening of December 13 when near midnight they met up with a “dark

complexioned man.”

In the meanwhile Doc Gibson went to

the police headquarters as a “stool pigeon for Sheriff Frank Emery. Gibson informed him that

“mischief was afoot.” Sheriff Emery sent out a detail to locate Sullivan and

Owen and followed them.

About a week later, Doc Gibson,

“after having made himself useful to the authorities,” attempted to rob of a

young, inebriated Swede at the

Darlington Rooming house on East Second South Street by impersonating being a

deputy sheriff. Gibson was arrested, tried, and sentenced to jail for the

crime. However while incarcerated he escaped and disappeared from this

narrative.

It was after midnight Saturday

December 14, when Sullivan and Owen agreed to accompany Garcia back to the

Kimball house to get something to eat and make plans get money on which they

could get out of town.. They left the Continental Saloon after midnight and

walked up Main Street past the Salt Lake Temple towards the old Kimball

property. After entering the house, Sadie Belcher admitted them into the

“humble little room,” where Garcia had been hiding out.

The three desperadoes were hungry

from drinking all day and having only eating bar food. Sadie Belcher cooked a

meal for them and set the kitchen table with a “repast of eggs, coffee, and

pie.” While the men were eating, Garcia produced two revolvers which he placed

on the table. They belonged to Tip Belcher who allowed Garcia the use of them.

Sullivan noticed that bullets for

one of the cartridges was too large and he whittled a bullet down as to fit the

gun, then he “slipped it into his pocket.” Garcia was said to have kept the

other weapon.

Over their meal, the men discussed

ways to get money on which to leave town. Sullivan related his plan to hold-up

a saloon, however Garcia objected to “highway robbery as too dangerous and

unprofitable.”

Sadie Belcher said they were only gone ten or fifteen minutes before returning to Kimball rooming house but would later change this story to say she did not see them again for several hours.

|

| McCornick Mansion |

Chapter Eleven

The Albany Saloon

Whether after leaving the Kimball

place or the McCornick house, Sullivan, Owen, and Garcia walked back down the

hill towards the Continental saloon. There Sullivan asked Owen where the Albany

bar was again, evidently only having been there once earlier on December 13.

Owen told him that the saloon was down near the Denver and Rio Grande depot and

Sullivan according to Owen said he was going to “hold-up the place.”

|

| Sanborn Fire Insurance Map 1898 |

Who robbed the Albany Saloon and

was involved in the shooting of Officer Ford now depended on which convict one

choses to believe. John Owen claimed that the three of them went to the Albany

saloon, with him only being a look out, never actually going into the bar, and

having run away after he heard a gunshot. Owen maintained that it was Garcia

and Sullivan who had robbed the saloon while he only went along as a look out.

The facts were that both of the thieves who held up the Albany Saloon had

revolvers but only Sullivan and Garcia were reported to have had weapons

according to Sadie Belcher’s testimony.

Joe Sullivan however claimed that

he left Garcia and Owen shortly after leaving the Continental saloon and went

to the Oregon Short Line rail yards to try and catch a empty box car out of

town towards Ogden. Although Sullivan had only but one set of clothing, the

gray suit given to him at the time of his release from prison, neither of the

bandits were identified as wearing such an outfit.

Initially the Albany bartender who

was held up reported that one of the bandits was “swarthy” and seemed to be a

“foreigner” and also so stated that one of the robbers was shorter than the